Over the past few years of working in academic medicine, one aspect of professional development that confounded me was the notion of fame and it's not too distant cousin, fortune.

Years of coaching elite athletes exposed me to their world of notoriety and wealth — their careers in entertainment are fundamentally rooted in our societal value of celebrity. However, I only recently came to appreciate that a similar hierarchy of recognition exists in spine surgery (and presumably other medical specialties). In this short commentary, I seek not to dissect the psyche of fame seekers or pass judgement on those striving for wealth; rather, I offer my observations as a non-surgeon to residents, fellows and faculty with these ambitions.

What is fame and fortune in academic medicine?

Despite a relatively short professional experience in medicine, I have enjoyed the privilege of working with/for some highly respected — and perhaps even, famous — spine surgeons. These thought leaders possess name recognition from their publications (books and papers), special technical skills or pioneering advances. Such notoriety does not typically lead to the broad benefits enjoyed by entertainment celebrities; rewards in the academic realm include funded trips (flying coach) to lecture or lead labs, consulting gigs with industry, and competitive salaries at their home institutions.

In addition to these individual perks, staffing world-renowned surgeons on your faculty may also benefit the department. Residents tend to prefer training with these persons because it lends credibility to their future careers and fellows seek them out for the specialized technical training. Hospitals may see additional financial profits because surgeons with international reputations can attract interesting cases from patients outside of the normal catchment area or those with the means to pay cash.

Fortune is a little more difficult to discern in medicine because the scale is varied and wide. Factors such as type of practice, geographic location, multi-variable metrics (e.g. RVUs, patient satisfaction scores, etc.) and reporting sources can all contribute to a physician's remuneration. For the purpose of this discussion, the 2017 national median income for a neurosurgeon working at the 50th percentile ranged from $629,550 to $704,170(1) while the 2015 median salary of an orthopedic spine surgeon was $736,710 (2). In comparison, the national median household income for November 2018 was $63,554 per annum.(3) These numbers do not reflect ancillary forms of income. While smart hospitals invest in performance bonuses based on transparent metrics, a small cadre of surgeons earn six figure fees or more for industry consulting, teaching or expert testimony. I am certainly not suggesting that highly trained neurosurgeons take a pay cut; these numbers only serve to remind us that wealth, fair compensation and other financial comparisons are all relative.

The path to fame and fortune

There is no fool-proof, verified formula for becoming a rich and famous spine surgeon. Rather, there are strategies and cautions, which require deliberate attention to maximize chances of success while minimizing collateral damage. Before going down this path, of course, it is important to define and prioritize what is most important to you. First, fame and fortune are cousins, not a partnership. In other words, you may get both but it is also possible to get one without the other. Second, both instances exist on a sliding scale. You may be the most famous surgeon in your town (in relatively short time) simply by being competent and doing the occasional news interview. Getting to the national or international stage will require a different time and effort commitment.

With respect to fortune, wealth is somewhat subjective. A salary of $500,000 is great by most American standards where first-quarter data for 2019 reported a median weekly earnings of $905 or about $47,060 per year (4). However, many spine surgeons are expecting compensation well north of that figure ($1M or more). Under these circumstances, private practice is likely the most expedient path towards a high payday: you will have greater control over your cost structures and schedule (versus academia) thus ensuring a high rate of return on your time allocation.

Once you know your standards and priorities, it is useful to set a time-line. Returning to the examples above, fortune can come relatively quickly once out of residency. Hospitals that pay well because of location (e.g. less desirable geography) or those that believe in sharing down-stream revenue via performance bonuses are readily identifiable. Fame, on the other hand, typically requires a longer path with less clarity because it either demands a deliberate focus on becoming the best at something or, the luck of someone else's misfortune landing in your emergency department (e.g. a celebrity breaking her neck in an accident).

Knowing where to commit the limited hours and minutes of your day is one of the most important decisions to make. Ambitious goals are certainly achievable, but for most of us, some other area(s) of life will suffer. Every hour in a lab or spent writing a paper equates to one less hour with your family; every sporting event attended is time lost for professional development. In coaching my physicians, I want to know where spouses and children fit into the equation. More importantly, aspiring stars should have that conversation with their families because they too will carry the burden of missed dinners, concerts, games and celebrations.

Keep in mind, personal circumstances can change. Spending 75 days on the road attending conferences or meetings might be easy while single or without children; however, should your home situation suddenly change, so might your priorities.

What follows is a list of truisms that I have learned from my work in both academic medicine as well as other professional industries. Physician interactions elicited some recommendations while colleagues and mentors passed forward other insights.

Considerations in Pursuit of Fame and Fortune

1. ROI: Academic Medicine vs. Private Practice. Private likely pays better (at least out of the door), but in terms of building your reputation, producing disciples who credit you with being a great teacher is the best return on investment. Residents and fellows who respect your talents will laud your name in a variety of settings throughout cities across continents; grateful patients may fill out satisfaction surveys or drop you a hand-written note. (Harry van Loveren, MD).

2. Define your commitment to non-clinical (e.g. uncompensated) efforts. Even with protected time (typically one day a week), that isolated carve-out will not suffice. Being an academic requires effort in between cases, at night and on weekends. Determine the time sacrifices that are both realistic and required to build your academic portfolio. (Volker Sonntag, MD)

3. Budget your finances for traveling to conferences, meetings and any other event that can advance your knowledge and network. In addition to the monetary expenditure of plane tickets, airport transfers, hotels, food, etc., also budget time away from work duties (e.g. weekend calls that your partners must take) and family obligations (e.g. missed social events). What are the “actual costs” for these various efforts?

4. Discuss your priorities with those impacted by academic pursuits. First, transparency is incredibly crucial. Acknowledge worst-case scenarios such as working late, diminished salaries, travel, etc. Second, have a plan that enables you to balance professional necessities with quality family activities such as anniversary parties, birthday celebrations, athletic games or school performances. If you cannot devote equal time to competing priorities, how can you ensure the quality of limited time? (Juan Uribe, MD).

5. Pick an area of interest and become an expert. Strategically thinking, avoid popular disciplines where others are already well established — or, if thought leaders do exist, they are beyond the prime of their careers. Next, read every paper on that subject thus establishing your baseline knowledge before exploring research questions. (Harry van Loveren, MD)

6. Publish, publish, publish. The only way to have ownership of your ideas and establish a reputation as a thought leader is by publishing your work.

7. Concurrent to publishing, work your way up the speaking ladder. It may begin with poster presentations, but ultimately, your goal is to become an invited keynote speaker and visiting professor. Count the free travel as a bonus! (Multiple chairmen and spine surgeons).

8. Industry wants to work with surgeons — they need expert input for product design, improvement and verification. The benefit, besides prestige of helping advance the field, is the potential for financial gain. In order to get the attention of companies, you must first be recognized (by your peers) as a thought leader, which comes from publishing and presenting (#6 and #7). Not only is it good business practice for companies, it is also the necessary to avoid Stark Law violations.(5) (Matt Link, President of NuVasive)

9. Identify and formalize mentor relationship(s). Great mentors serve two specific functions, especially for junior faculty. First, they guide your research by helping you navigate question formulization and methodologies. Second, selfless mentors will open doors for you that would otherwise be difficult to access such as study groups that increase your data resources, committee assignments that raise your stature or funding sources to sustain projects.

10. Establish a trusted team around you. As an addendum to finding mentors (#9), create a team of technical experts to distribute the workload and solidify any personal areas of weakness. Add a biostatistician to help run your numbers; include a good writer if English is not your native language; or find a methodologist to strengthen your study design. Include medical students or residents on the team so that they have an opportunity to learn and contribute to the field.

11. Know what questions to ask. Some people simply have an innate ability to ask the right questions thus leading to novel insights. Others need help cutting through the clutter and seeing opportunities. Your team (#9 and #10) should provide a good sounding board for this process.

12. Learn the basics of finance. In a private practice arena, there will likely be an accounting person (e.g. CFO) who manages the cash flow of the business (or an administrator in an academic setting). Regardless of the organizational structure, you should know the fundamental rules of running the shop. Understanding how overhead is covered, the types (and coverage) of liabilities, profit sharing, etc., will protect everyone within the company.

13. Have trusted experts guide your business decisions. Remember, medicine is your area of expertise and people come to you for specific answers related to their brain or spine. Similarly, you should run major decisions by an outside party for unbiased, objective advice — especially legal or financial matters.

14. Enjoy and appreciate the people at your work. In a word, culture may be the most important consideration when choosing a place of employment. Given the amount of time surgeons spend at the hospital, a happy environment typically beats money because the amount of salary required to put up with miserable working conditions is rarely paid.

15. Show up and do your job. (Harry van Loveren, MD).

The pursuit of fame and fortune exists in medicine similar to many other professions. The paths can be isolated or combined. Regardless of this choice, spine surgeons should fully prepare for the hard work, sacrifices and commitment required to achieve their goa(s). Academic Medicine, while not guaranteed, represents one of the more optimal tracks to fulfilling both outcomes. Thoughtful and deliberate efforts researching a topic of interest can lead to publications thus establishing your expertise. Having a respected reputation on a given subject can build a demand for speaking engagements. While you may not be a household name for the general population, within the neurosurgical field, these academic activities will put you in the category of fame.

In addition to free travel, opportunities to secure financial rewards from your expertise are also plausible. Industry is both willing and capable of compensating highly reputable surgeons for teaching, product development or other consulting services. In this regard, fortune can equate to sums in the six or even seven figure range. Surgeons who are inclined to pursue the academic tract for material gains should do so under caution. The road is long and arduous with no guarantees; but with the right mindset, it can also be a satisfying professional journey.

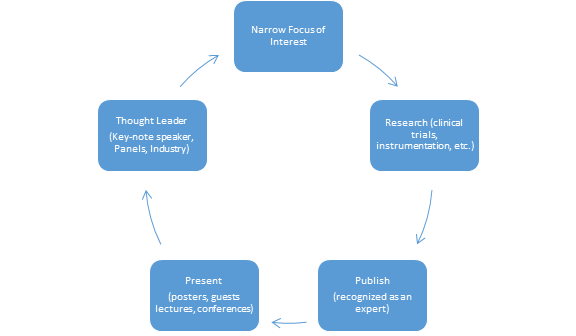

Figure 1: Traditional Path To Fame

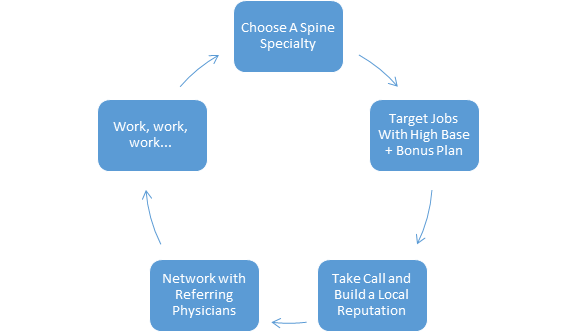

Figure 2: Traditional Path To Fortune

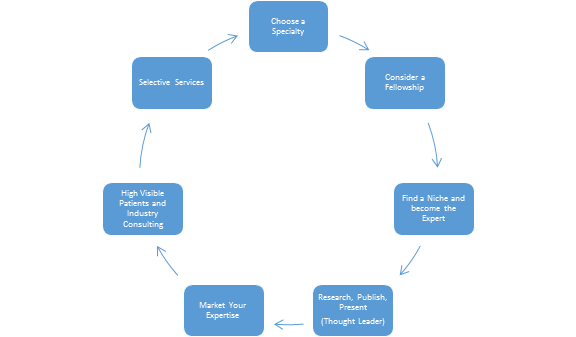

Figure 3: Traditional Path to Fame and Fortunre

1. Benzil DL, Zusman EE. Defining the Value of Neurosurgery in the New Healthcare Era. Neurosurgery. 2017;80(4S):S23-S7. doi: 10.1093/neuros/nyx002.

2. Wood M. 55 Statistics and issues for neurosurgeons and orthopedic spine surgeons--compensation, global device market and more. Becker's Spine Review. 2015.

3. Gordon Green JC. Household Income Trends June 2018. Virginia: Sentier Research, 2018.

4. Usual weekly earnings of wage and salary workers first quarter 2019 [Internet]. U.S. Department of Labor; 2019; April 16, 2019 [cited June 25, 2019]. Available from: https://www.bls.gov/news.release/pdf/wkyeng.pdf

5. Kanter GP, Pauly MV. Coordination of Care or Conflict of Interest? Exempting ACOs from the Stark Law. The New England journal of medicine. 2019;380(5):410-1. Epub 2019/01/31. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1811304. PubMed PMID: 30699326.